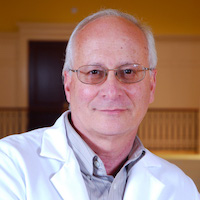

Dr. Steven Zeisel will be stepping down as the UNC Nutrition Research Institute’s director after 13 years, but he leaves behind a legacy that has helped shape a more comprehensive picture of nutrition.

The USDA regularly distributes a nutrition guide — once a food pyramid, now a plate — that provides the recommended daily intake for different food groups. But that cookie-cutter approach to eating, the idea that every person should consume a similar diet, ignores individual needs.

Dr. Steven Zeisel, director of the UNC Nutrition Research Institute and professor of nutrition at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, is one of the researchers looking to change that by pushing for precision nutrition — an approach that takes people’s “metabolic heterogeneity” into account.

“I was trained as a physician, and we were taught everybody’s about the same, but we know now that’s not true,” he says. “Every person has many spelling differences in their genetic code, and about 50,000 of those spelling variants make a difference to how metabolism runs.”

Zeisel’s interest in what would become known as precision nutrition started with choline, an essential nutrient that supports healthy cells and memory function, among other things. By the early ‘90s, textbooks stated that people didn’t need to eat choline because they produced it naturally. But based on what he knew about choline in mice, he wasn’t so sure. “I was lucky to ask if that was true,” Zeisel says.

Zeisel’s decades of choline research led to a new understanding of the nutrient, namely that it’s an essential part of people’s diet. But people’s genetic makeup — the spelling differences that inform metabolic heterogeneity — means some may need greater amounts of choline, through diet or supplements, than others.

That early work on choline went on to inform Zeisel’s interest in precision nutrition, which became the backbone of NRI’s work. Zeisel helped develop the institute’s focus when it opened in Kannapolis, North Carolina, in 2008. Today, Institute researchers concentrate on three areas of precision nutrition: genes, environment and microbiome.

As research moves away from a uniform diet, it will be important to get a more comprehensive view of people. “That’s the next phase of precision nutrition,” Zeisel explains, “to integrate what we know and to give you a much more sophisticated estimation of whether you need more or less of specific nutrients.”

As a result of NRI’s work and Zeisel’s specific efforts, precision nutrition has received more attention lately from the National Institutes of Health. “They’ve set aside $155 million to spend over the next five years on research projects,” Zeisel says. “I’m hoping that NRI is capable of leading and being an important component of this major effort.”

With that feather in his cap, Zeisel is preparing to step down as director. “NRI’s bringing in millions of dollars of research support. It’s providing jobs for people who live in the [Kannapolis] community,” he says. “It’s gotten a good start, and it’s brought something to the University that we didn’t have before it was created.”

In situating NRI’s prominence in the precision nutrition field, he leaves an immense legacy behind. But he knows it wasn’t a solo effort. “I think I’m happier that many of the young faculty I was able to hire are doing very well in many areas of nutrition,” he says. “Their futures are really the legacy I’m most pleased to have contributed to.”

Zeisel’s next chapter includes focusing on his company, SNP Therapeutics, which aims to design and produce the comprehensive genetic tests necessary to achieve a fuller picture of choline deficiency. “We are trying to develop a test that health professionals could use in their office to determine whether you have low greater requirements for choline,” he says.

Zeisel is also looking forward to more leisure time, including tending to his collection of 80 bonsai trees. “I’ve never had time,” he says. “You’re on a treadmill in science.” While his research has fueled his curiosity, prompting the important questions that led to the breakthroughs he’s achieved with choline, he’s looking forward to the “peace and quiet and creativeness of trying to make good bonsai trees.”